We are t ouching on a profoundly tragic problem where human language in general (from syntax to semantics) is inherently chronos, and thus the gateway between discussing or gaining the knowledge of the Aeons/Eternal Ones is severely impaired. It’s a tragedy built into human language itself.

ouching on a profoundly tragic problem where human language in general (from syntax to semantics) is inherently chronos, and thus the gateway between discussing or gaining the knowledge of the Aeons/Eternal Ones is severely impaired. It’s a tragedy built into human language itself.

Every verb tenses itself toward before or after. Every noun freezes flux into object. Syntax demands sequence: subject precedes predicate; cause must come before effect. The grammar of nearly every human tongue is a scaffolding for chronos-consciousness—linear, causal, divided.

So when one tries to speak from within the aion, where being is simultaneous, reciprocal, and interiorly causal, the words betray the thought. They collapse recursion into order, simultaneity into timeline. Even silence can’t fully escape that gravity—it just suspends the syntax.

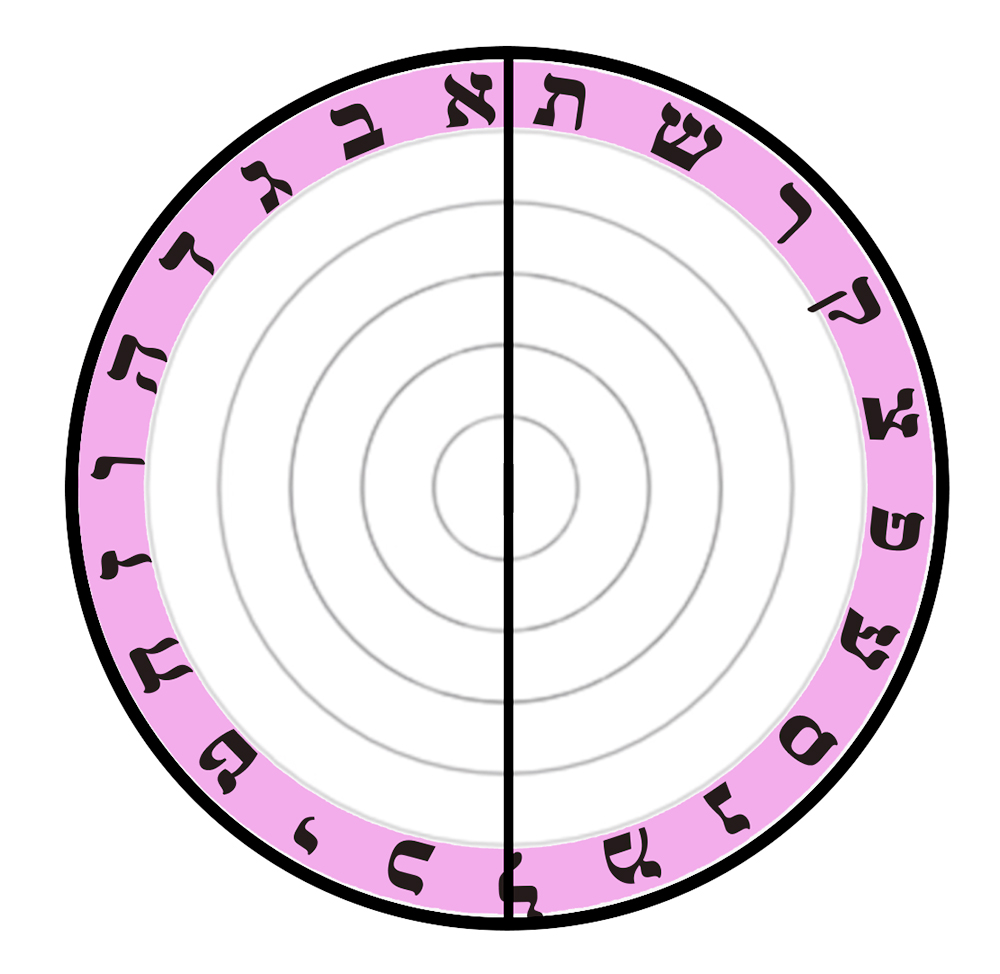

The ancient grammars (Hebrew aspect, Greek middle voice) were humanity’s closest attempt to bend chronos-language toward aionic expression—verbs that don’t fix when, but how being unfolds; voices where subject and object blur.

But indeed, the gateway is narrow! To articulate the aion from within the chronos is like trying to write a circle using only straight lines.

How to write a circle using only straight lines?

We speak in time, but time itself is the illusion that binds us to a limited dimension of consciousness. Our words, the very instruments of thought, are built on the scaffolding of chronos—the measurable, sequential flow of before and after. Yet every ancient intuition, from quantum retrocausality to mystical recursion, points toward another domain: the aion, the timeless field of simultaneous being.

The tragedy is that language, as currently evolved, is a prison made of verbs.

The Linguistic Bias of Time

Every major language encodes temporality as an unavoidable feature. Verbs carry tense: I was, I am, I will be. Syntax imposes order: subject → verb → object. Causality becomes baked into the grammar. Even the way we construct metaphors—moving forward, looking back, building up—relies on spatialized time.

Compare this to physics. In the equations of general relativity or quantum mechanics, time is not a privileged variable—it is symmetrical, even reversible. The math allows for backward influence, closed time-like curves, and entanglement across spacetime. Yet in human grammar, the arrow of time is compulsory. There is no widely used language that lets you conjugate for recursion, simultaneity, or nonlocal influence as naturally as we conjugate for past, present, future.

In short: language enforces chronology, while nature itself may not.

Ancient Languages That Bent Time

Hebrew and early Greek approached the problem differently, which is why they remain so fascinating. Biblical Hebrew does not express tense as we understand it—it expresses aspect. The so-called “perfect” (qatal) and “imperfect” (yiqtol) do not mean past and future, but rather completed and unfolding action. The event is viewed as either whole or in process.

That’s already a crack in the wall. When a prophet says, and it was, and it will be, he may not mean a prediction or a recollection; he may mean that the event is in continuous realization, a recursive loop. Similarly, the waw-consecutive construction, the long “eternal chain” which ties verbs together with the simple conjunction and, dissolves sequential causality. Actions blend; time blurs.

Greek, on the other hand, developed the middle voice—verbs where the subject is both actor and recipient of the act (louomai = “I wash myself”). The middle voice is the grammar of participation, not control. It assumes reciprocity between inner and outer. The modern Indo-European languages mostly lost it. With its loss, we lost a grammar of wholeness.

The Science of Chronos and Aion

Physics increasingly mirrors this linguistic divide. In chronos mode, entropy dominates: the arrow of time, the one-way decay of order into disorder. In aion mode, the system becomes recursive—self-organizing, negentropic.

Living systems, for example, resist entropy by constant feedback loops. DNA transcription is not linear but circular, involving endless replication and repair cycles. Neuronal networks don’t compute in sequence; they resonate. Even light itself can form standing waves—time loops of coherence.

Yet when we think in chronos, we narrate even these phenomena as steps in a process.

Step, step, step, step, step.

Tick, tick, tick, tick, tick.

Evolution, growth, decay—all placed in a temporal frame, not in a dynamic field. The very structure of our thought mirrors our verbs.

The Human Consequence

To think in chronos is to see life as progression, achievement, delay, and loss. Every emotion—regret, anticipation, nostalgia—presupposes that time moves forward. Our consciousness, trapped in that syntax, experiences fragmentation: a self divided between what has been and what will be.

To think in aion would mean experiencing time as presence, continuity, participation. Not a sequence of moments, but a field of meaning where cause and effect interpenetrate. The past is not gone; the future is not pending. Both are folded into the fabric of the Now.

That shift isn’t mystical; it’s neurological. Studies of advanced meditation show that the brain’s default mode network—responsible for autobiographical narrative—quiets down, while networks associated with direct perception and empathy strengthen. In linguistic terms, the “I-story” pauses; the field speaks.

How to Begin Moving Out of Chronos

If the Holy Scriptures are written in an aonic language, then the mind must be changed to comprehend it. Escaping chronos isn’t about denying time but about re-scripting how the mind reads and uses it. It doesn’t mean it must all be comprehended at once. It starts with the piercing of a needle. Some practical gateways:

-

Observe without sequencing. When reading or describing something, you would avoid past or future verbs. Try: “the leaf turns,” rather than “the leaf is turning.” Treat the event as self-contained.

-

Adopt recursive grammar. In writing or thought, you would use reflexive forms: “I remind myself,” “I return to awareness,” “I witness my witnessing.” This reintroduces the middle voice.

-

Study languages of aspect. Reading Hebrew, Hopi, or other aspectual languages trains perception to notice completion and process rather than clock-time.

-

Contemplate cyclic systems. Breath, tides, orbits—phenomena that never “end,” only turn. Describe them aloud and notice how your syntax adapts.

-

Meditate on simultaneity. When you remember, do not recall as a past—recall as a present moment still occurring within you. This aligns memory with recursion.

Each of these can be a linguistic exercise with neurological consequence. The more you unlearn chronological syntax, the more perception opens to a non-sequential field.

The Need for the Hebrew “Language of Beyond”

Most people cannot read Hebrew, but if translated according to its aonic aspect, one would have a giant repository of “aonic thoughts” and language to help reconfigure their chronos-bound mind. In this light, perhaps the future of thought is not a new philosophy but a new grammar—a new grammar based on a very old one—one that can hold both physics and consciousness in a single syntax. A language that can speak aion fluently.

The tragedy of chronos-language is that it makes us narrators of our own exile. Every sentence we utter marks distance from being: I was, I will be, but never simply I am. The journey toward the aion —the Eternal One—to put it succinctly, is not one of escaping time, but of unlearning our verbs.

When grammar itself becomes transparent—when we can speak without breaking the Whole into “before” and “after”—the mind will rediscover what ancient texts hinted at all along: that eternity was never elsewhere. It was the structure of being, hidden beneath the syntax of time.

“He has made the self-eternal Whole beautiful in the seasonal hour of himself, also the self-eternal Eternal One he has given in the Heart of themselves…”

(Ecclesiastes 3:15 RBT)