Atemporal Causality (n.) — A mode of causation wherein the cause-effect relationship transcends linear temporal sequence, such that the cause and effect are not bound by chronological order. In this framework, causality operates outside or beyond time, allowing effects to influence causes retroactively and causes to be simultaneously present with their effects. Atemporal causality is characteristic of a non-linear, recursive, or participatory temporal ontology—such as the aion of the NT—where divine action and revelation unfold within an eternal “now,” integrating past, present, and future into a singular, coherent event. This concept challenges conventional mechanistic understandings of causality that assume strict temporal precedence and succession, proposing instead a dynamic interpenetration of temporal moments in a unity sustained by divine love (agape) and transcendence.

The difference between an Aonic circular framework vs. a “lineareality” is that in a linear reality there is only an ever-changing “point” on a linear timeline, and it never ceases to change its state. There is no beginning, and there is no end. To a linear line, you don’t matter. You hardly exist. In fact, you don’t really exist at all. You are external and disposable. You are not. Linear reality is a cursed “time is money” or “live in the moment” scheme because all there is, is the moment. There can never be rest. In a circular framework however, there is self-meaning, self-determination, and best of all, a real potential for completion and perfection. A real rest. In other words, you not only matter and exist, but are essential to the All.

Any child can tell the difference between a circle and a line. These are immutable ideas. Nevertheless the classic example of James 3:6 shows that scholars decided to translate a “circle” as a “line”:

τὸν τροχὸν τῆς γενέσεως

the wheel of the genesis

In every modern translation, including the KJV, this is rendered “the course of life” or “the course of nature.” Even the literal ones (YLT, LSV, LITV, BLB), with exception to Julia Smith’s, translate this as a linear course. The course of life is an idiom understood as a linear concept where the underlying model is one of linear temporal causality. Events unfold in a sequence. Birth precedes childhood, which precedes adulthood, which precedes death; in nature, seed precedes growth, which precedes decay. The sequence runs in one direction. It does not allow return to the starting point, only forward movement. Earlier stages generate or condition later ones. Childhood leads into adulthood, planting leads to harvest, cause leads to effect. That’s why in English (and in its Latin sources) “course” doesn’t just mean “time passing” but “time unfolding in an ordered, directional way” — like a river current or a race track. But a wheel is circular and revolving. This is one of the best illustrations of the difference between what is written and the interpretive bias that has prevailed in two thousand years of translations. It is often referred to as “dynamic equivalence.” Yet, how is a linear progression dynamically equivalent to a revolving circle? Anyone can see how this dramatically affects the outcome of what is conceptualized by the reader. It is not small. I believe the difference between lines and circles is learned in preschool, if I’m not mistaken.

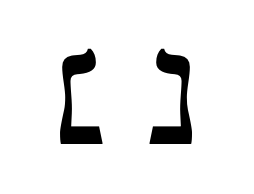

Why Hebrew Was Written from Right to Left?

The right-to-left writing direction originated primarily with the Phoenician Hebrew script (c. 1050 BCE), the roots of Biblical Hebrew maintained through Paleo-Hebrew into the square Aramaic-derived script still used today. Perhaps it was done this way because of the practicality of chiseling the letters with the hammer in the right hand. On the other hand—pun intended—the Prophets had a lot to say as coming from the Right Side. The “right,” “front,” and “east” are all words which encode the front of time for the prophets. The prophets were masters at encoding things into riddle, enigma, and dark sayings. This is not particularly pleasing to everyone, and sometimes it is frustrating to the point that one resorts to crooked ways to try to force out the secrets (e.g. Philistines with Samson). This was the way of the Hebrew prophets. They didn’t write for the dirty crooks, they wanted to write for the Just. So for them “the East” and “the Right Side” was “the Future” and their source of enlightenment, vision, and knowledge. For them, they weren’t meaning to record what they heard or saw. They were meaning to transmit truth and knowledge backwards. What they heard was a pre-existent “voice” from far ahead. From this other sayings were encoded, such as “he who has an ear, let him hear.” If one is deaf in the prophetic sense, he cannot hear anything from ahead. Perhaps his right ear was cut off? In that case, all one is able to hear is “in the beginning” far, far behind and not “in the head/summit” up ahead.

If a book of life is living and active, live and real-time, you play an integral role. Such a book would be easy to decide and act on, because there would be no gray area within even the finest point. It’s either alive or dead. On the other hand, if such a book existed and was covered up, turned into a darkened gray area, completely unwound and flattened into temporal linear frameworks that were never intended, well, it all remains to be seen, and even that becomes part of its own living story and testimony…

Abstract

Biblical Hebrew, a language often marginalized in linguistic typologies due to its lack of tense and sparse case system, may in fact represent a profound grammatical architecture of an alternative temporal consciousness. When analyzed through the lens of Aonic language theory—a speculative linguistic model grounded in Möbius temporality, causal recursion, and non-linear event topology—Hebrew emerges not as primitive, but as prototypical. This paper proposes that Biblical Hebrew functions as a proto-Aonic language: a script of eternal recurrence, causal reflexivity, and atemporal narrative agency. Drawing from aspectual verbal morphology, syntactic recursion, and the absence of accusative time/place as well-documented by Theophile Meek (1940), we argue that the Hebrew Bible is structurally designed to be a “living and active” Möbius-text—designed not to record history, but to enact sacred reality in real time.

1. Time Folded: The Aonic Premise

The theoretical Aonic language presumes a temporal structure that is not linear but looped, folded, or recursively entangled. Events do not proceed along a timeline but emerge from interwoven causal matrices. Under such a paradigm, grammar must:

-

Abandon tense in favor of event topology

-

Replace fixed pronouns with temporal multiplicities

-

Supplant spatial coordinates with resonant zones

-

Encode agency as distributed across time

This grammar yields a language capable of articulating Möbius-like narratives, wherein identity, action, and causality cannot be temporally situated without distortion. This feature underlies the perennial difficulties in constructing a strictly chronological sequence—most famously in the Book of Revelation—where attempts at linear arrangement inevitably misrepresent the text’s recursive structure. Hebrew, as we shall demonstrate, astonishingly anticipates this very logic, encoding an atemporal dimension in its participial and aspectual systems.

2. Aspectual Architecture: Time Without Tense

The study of tenses and moods in Hebrew syntax has historically been overlooked, as noted by Bruce K. Waltke and M. O’Connor in Biblical Hebrew Syntax. They point out that “the question of tenses and moods, which is both the most important and the most difficult in Hebrew syntax, was neglected by ancient grammarians” (§111(2), p. 354), with early exegetes and translators relying more on intuition than a precise understanding of these forms. This neglect stemmed from a lack of systematic analysis, leaving tense forms in poetic sections to be used in a “rather haphazard fashion” (§111(2), p. 354), revealing a gap in early scholarly engagement that persists as a challenge.

No Satisfaction

Even today, the complexity of Hebrew tenses and moods remains a formidable obstacle, with Waltke and O’Connor acknowledging the difficulty in achieving precision. They observe that “many forms which are difficult and even impossible to explain satisfactorily” (§111(2), p. 354) persist, particularly in poetic contexts, and despite their efforts, the authors admit the limitations in fully resolving these issues.

Wilhelm Gesenius (1786–1842), often hailed as the “master” of Hebrew grammar, failed to recognize the fundamentally aspectual (rather than strictly temporal) nature of the so-called “imperfect” and “perfect” verb forms, thus attributing to them inexplicable “peculiar phenomena” when they defied a purely temporal interpretation. By imposing a temporal logic upon the text, he inadvertently obscured the inherent atemporality of these forms:

The use of the two tense-forms…is by no means restricted to the expression of the past or future. One of the most striking peculiarities in the Hebrew consecution of tenses is the phenomenon that, in representing a series of past events, only the first verb stands in the perfect, and the narration is continued in the imperfect. Conversely, the representation of a series of future events begins with the imperfect, and is continued in the perfect. Thus in 2 K 20, In those days was Hezekiah sick unto death (perf.), and Isaiah… came (imperf.) to him, and said (imperf.) to him, &c. On the other hand, Is 7, the Lord shall bring (imperf.) upon thee… days, &c., 7, and it shall come to pass (perf. וְהָיָה) in that day…

This progress in the sequence of time, is regularly indicated by a pregnant and (called wāw consecutive)…

(Gesenius, Hebrew Grammar §49.)

What Gesenius calls a “progress in the sequence of time” is better understood as a progression of discourse events within a narrative world. The waw-conversive (ויהי, ויאמר, etc.) is less a marker of time and more a structural operator that realigns the aspect of the verb to continue a narrative sequence. It also maintains thematic cohesion within a frame of realization (for vav-conversive imperfect) or projection (for vav-conversive perfect).

As such, the so-called “change” of tense is a discourse strategy, not a grammatical expression of linear time.

Imposing a temporalist model—past leading to future, or vice versa—is a category error grounded in Indo-European assumptions. It is a hermeneutic distortion, not a linguistic fact. Nearly all Hebrew scholars default to this framework, often because no viable alternative seems available. If verb structure in Hebrew encodes a recursive ontology (events are realized through speech, narrative, and participation), then collapsing that into mere chronology erases the sacred recursive grammar.

Biblical Hebrew famously operates without grammatical tense (Gesenius, Hebrew Grammar/106). Instead, it distinguishes between completed (qatal) and incomplete (yiqtol) actions. If an eternal language with an eternal topological aspect, we must understand each binyan not simply as grammatical categories but as functional transformations of agency and causality within a linguistic feedback loop. Each binyan alters the vector of action, location of agency, and direction of recursion in the event structure.

We treat each binyan as a morpho-causal function applied to a verb root (√), transforming the flow of agency and participation of subject/object in the act-event loop.

- Qal (קל) — F(x) → Base Actuation

- Function:

F(x) = x - Agency: Direct, unadorned.

- Causality: Linear action flows straightforwardly from agent to object/act.

- Participation: External: The subject initiates; the object receives.

- Aonic view: The base level of causal instantiation. A single fold of the loop.

- Ex. שבר (shāvar) — “he broke [something]”

The act simply is.

- Function:

- Niphal (נפעל) — Self-Folding Function

- Function:

F(x) = x(x) - Agency: The subject experiences the action upon themselves or is passively affected.

- Causality: The agent becomes the recipient of its own act.

- Participation: Internal: Loop closes on self.

- Aonic view: The event is recursive in the self. The act loops back on the subject; the doer and receiver merge.

- Ex. נשבר (nishbar) — “he was broken”

The agent and patient converge. The act returns.

- Function:

- Piel (פעל) — Amplified or Repeated Function

- Function:

F(x) = xⁿ - Agency: Intensified, deliberate, or repeated.

- Causality: Agent amplifies the act beyond normal bounds.

- Participation: External, but expanded in force or scope.

- Aonic view: Resonant feedback—recursion deepens. The act echoes stronger or more forcefully.

- Ex. שבר (shibber) — “he smashed”

The act echoes, not just occurs.

- Function:

- Pual (פועל) — Passive of Amplified or Repeated Function

- Function:

F(x) = (xⁿ)* - Agency: Absorbed from an external amplifier.

- Causality: Object is shaped by intensified external act.

- Participation: Object locked in the resonant loop of action.

- Aonic view: Passive harmonics—being acted upon by the intensified loop.

- Ex. שבר (shubbar) — “it was smashed”

Echo received; form shattered.

- Function:

- Hiphil (הפעיל) — Causal Operator Function

- Function:

F(x) = cause(x) - Agency: Subject initiates a second-order act.

- Causality: Subject causes another to perform an act.

- Participation: Meta-agent; insertion of will into another loop.

- Aonic view: Loop initiates new loop—a generative recursion.

- Ex. השביר (hishbir) — “he caused to break”

Agent writes a loop into another.

- Function:

- Hophal (הפעל) — Passive of Causal Operator

- Function:

F(x) = caused(x) - Agency: Subject is the outcome of someone else’s Hiphil.

- Causality: Act occurs as an embedded recursive operation.

- Participation: Passive but within an active loop.

- Aonic view: The result of recursive causation; passive node in a nested loop.

- Ex. השבר (hoshbar) — “it was caused to break”

Agent disappears; recursion remains.

- Function:

- Hithpael (התפעל) — Reflexive Recursive Function

- Function:

F(x) = x↻x - Agency: Subject acts upon self in a patterned or ritual form.

- Causality: Looped reflexivity with intent or rhythm.

- Participation: Full self-involvement in an internalized pattern.

- Aonic view: The recursive subject; the act of becoming via internal mirroring. The action folds back repeatedly on the self, forming a ritual loop.

- Ex. התאשש (hit’oshash) — “he made a man of himself” (Isa. 46:8)

The loop sanctifies its own form.

- Function:

| Binyan | Function | Agency | Causal Type | Aonic Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qal | F(x) = x |

Direct | Linear | Root actuation |

| Niphal | F(x) = x(x) |

Reflexive/Passive | Recursive internalization | Loop on self |

| Piel | F(x) = xⁿ |

Intensified | Resonant expansion | Recursive intensification |

| Pual | F(x) = (xⁿ)* |

Passive (Piel) | Resonant reception | Echoed causality |

| Hiphil | F(x) = cause(x) |

Causative | Nested loop initiation | Creator of recursive loops |

| Hophal | F(x) = caused(x) |

Passive (Hiphil) | Nested passive recursion | Receiver of embedded act |

| Hithpael | F(x) = x↻x |

Reflexive/Reciprocal | Ritualized self-recursion | Self-generative loop (rare Hishtaphel as self-degenerative) |

The lack of the accusative of time and place is not a deficiency—it is a topological reorientation. Actions in Hebrew are not anchored to past or future, but to states of completeness within a causal manifold. A qatal verb may appear in future contexts, while a yiqtol form may invoke past prophecy—because the grammatical reality is aspectual, not chronological.

This mirrors Aonic event-markers like:

-

⊛ (“bootstrap causality”)

-

∴ (“structural consequence”)

-

∞ (“eternal coexistence”)

Niphal as a True Middle Voice

Hebrew verbs do not tell when something happens. They tell how the event participates in the broader loop of divine narrative. Apart from an aonic frame, the function of the verbs collapse and become very difficult to understand. For example, Gesenius noted that earlier grammarians categorized Niphal as simply the passive of Qal (e.g., שָׁבַר “he broke” → נִשְׁבַּר “it was broken”). But this analysis collapses the reflexive and recursive dimensions into a linear, Indo-European-style passive—imposing a foreign structure on Semitic morphology. Gesenius already recognized that this was a category mistake. He observed:

“Niphʿal has, in no respect, the character of the other passives.”

In fact, he appeals to Arabic (ʾinqataʿa) to show that Semitic languages retain a category for reflexive middle structures distinct from mere passives. He notes a reflexive priority:

“Although the passive use of Niphʿal was introduced at an early period… it is nevertheless quite secondary to the reflexive use.”

This places reflexivity at the heart of Niphal’s logic—precisely in line with our interpretation that Niphal embodies a loop-back structure: the agent as both doer and recipient. In the Aonic model, Niphal marks the first deviation from linear temporality and external agency (Qal). It introduces folding—where the action loops back upon the subject:

| Qal: Act done → object |

| Niphal: Act done → returns to agent |

This loop begins the process of internalization, which deepens as we move through the binyanim (Piel → Hithpael). The confusion by early grammarians is not merely taxonomical; it stems from a deeper misreading: they imposed a linear causality on a non-linear grammatical structure and sought to assign chronology where the grammar encoded recursion. Niphal occupies a grammatical space that Indo-European grammars typically lack—a true middle voice that is neither clearly passive nor active, but recursively enmeshed. Rather than seeing scholarly confusion about Niphal as a flaw in the grammatical tradition, we can interpret it as evidence of the inadequacy of temporalist models when applied to Hebrew. Niphal resists such models because it is, structurally and ontologically, recursive.

Hithpael as a Self-Generative Dialectic

“And mighty ones is saying, “I have given to yourselves here all the self eternal grass of a seed seed, who is upon the faces of the entire Earth, and the entire Tree whom within himself is a fruit of a tree of a seed seed to yourselves, he is becoming food.”

(Genesis 1:29 RBT)

Whereas Niphal involves the subject folding the act back upon itself—being “in the center of being”—Hithpael expresses a more deliberate, patterned, or ritualized self-action. It often implies the subject acting upon itself in a sustained or repeated manner, not merely undergoing an event passively or spontaneously.

Hithpael can also indicate reciprocal actions—actions performed mutually between subjects, or between one’s multiple facets. This is why it aligns well with the idea of “making your other self and your other self making you”: a form of internal (eternal) dialogue or self-generation.

-

Self-Generative Loop:

The function F(x) = x↻x suggests a recursive, rhythmic feedback loop—not just a simple return, but an ongoing process of self-creation or sanctification. -

Timeless Inner State:

Hithpael expresses a kind of transformative self-relation, where the subject is both the agent and the recipient in an intentional, ritualized cycle, evoking a deeper inner dimension than Niphal’s more spontaneous reflexivity.

In the dualistic realm of “good and evil,” where “self” and “other” are conceived as distinct but interacting realities, the Hithpael conjugation can be viewed as a “seed-seed” structure—an interplay or oscillation between selves within the same subject—a concept that explains the use of the Hebrew dual (e.g. dual heavens, dual-waters, dual potter’s wheel, dual-tablets, dual-womb, etc).

-

Back-and-Forth Movement:

The recursive reflexivity of Hithpael (F(x) = x↻x) models a dialogic loop where the self is both agent and recipient, speaker and listener, cause and effect within a continuous cycle of self-interaction.

This is the “seed” sowing itself into another “seed,” creating a generative back-and-forth or reciprocal becoming. -

Self as Dual Process:

Rather than a static identity, the self here is a dynamic multiplicity, where one aspect of self acts upon or “becomes” another, generating transformation and growth (or death) through internal relationality (e.g. the outer man projecting upon the inner man, the inner man projecting back upon the outer man). -

Aonic View:

This recursive loop reflects an atemporal “fold” of identity—beyond linear time, the (eternal) self is eternally in dialogue with its temporal self, creating an ever-unfolding “seed-seed” genesis.

Hishtaphel as a Self-Degenerative Dialectic

The notably rare, and thus difficult to grasp reflexive Hishtaphel form (a variation on Hithpael) is used primarily for “bowing down.” No one has had any sufficient explanation for the variation (cf. Ges. §75kk, unFolding Word Stem Hishtaphel).

The Hithpael binyan embodies reflexive, self-directed action—a “loop” of self-interaction that is fundamentally self-creative or self-actualizing. It can be seen in the “seed-seed” generative loop, where the self participates in its own becoming, transformation, or sanctification (e.g., הִתְקַדֵּשׁ hitkadesh “he sanctified himself”).

However, with a verb like השתחוה, the reflexivity is directed downward—a physical and symbolic bowing or prostration. This “bending” back onto oneself would also imply a recursive descent rather than ascent. Instead of mutual uplifting, the aonic dynamic here expresses a recursive feedback loop of descent: each act of bowing folds the self deeper into submission, subjection, and despair. This is a reflexive loop that generates a spiraling “bottomless pit” or abyss. The subject bows to itself repeatedly, each iteration amplifying self-subjugation or degradation.

While many Hithpael forms are “self-generative” loops fostering growth, ritualization, or sanctification (e.g., hitkadesh), the bowing form stands out as a “self-degenerative” loop where the recursion may be a descent into an abyss of despair.

From an Aonic perspective, this reflexive bowing can be understood as:

-

A recursive temporal loop without resolution—the subject caught in a Möbius strip of self-bowing.

-

The loop does not advance or resolve but folds back upon itself endlessly, intensifying the state of abasement or degeneration. This doubtless represents a spiritual abyss, a “pit” where selfhood is recursively diminished.

Therefore, in terms of the self, if a reflexive-generative process would “enlarge one’s territory” to an eternal existence (colossal), what would a de-generative process do it?

Diminish it to nothing.

3. Recursive Revelation: Möbius Semantics in Prophetic Texts

Hebrew prophetic literature collapses traditional narrative structure. The “future” is spoken as already occurred using the perfect/completed form; the past is reinterpreted in light of the present; and divine speech often functions as causative agent rather than commentary.

Consider the literal Isaiah 46:10:

“He who declares the back from the head, and from the front that which has not yet been made.”

This is not poetic metaphor—it is semantic recursion. The structure here reflects an Aonic Möbius:

-

Beginning causes End (↺)

-

End retroactively affirms Beginning (⇌)

-

The utterance is both prophecy and act (⊛)

This recursive quality imbues Hebrew scripture with a timeless operationality: each reading reactivates the text, looping the reader into its semantic causality.

Numbers 24:17, a prophetic oracle by Balaam traditionally translated in the linear fashion:

“I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near. A star shall come out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel…” (ESV)

Here, the verbs translated as “shall come” (דרך, dārach) and “shall rise” (קם, qām) are actually perfect forms in Hebrew. Yet they’re translated in most English Bibles with a future tense: “shall come,” “shall rise.” The verbs for “see him” and “behold him” are imperfect forms. This practice is rooted in the idea that in prophetic discourse, the speaker is asserting the certainty of the event’s eventual realization. But this seriously conflicts with the nature of the Hebrew Prophet as one who actually sees the future, not merely hears about it—hence “I am seeing him.”

In the Aonic (Möbius) reading, this is a case of semantic recursion. The perfect form does not simply denote “past” but encodes completeness in the speaker’s present—an ontological rather than chronological mark. The prophetic utterance itself is a performative speech-act that makes the event real. This collapses the distinction between future and past, creating a timeless operationality where prophecy is both prediction and enactment.

In other words, the perfect is not predicting a future that might happen; it is declaring an event that is already woven into the reality of the divine narrative. Its “completion” is ontological, not temporal.

“I am seeing him, but not now; I am beholding him, but not close at hand. A star has marched from out of Jacob, and a tribe has stood up from out of Israel…”

The traditional reading of Revelation 22:13 —

“I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end.”

— is usually interpreted through a linear, Indo-European temporal model, which imagines time as a line stretching from a beginning (creation) to an end (eschaton). Christ is then said to somehow be standing at both poles, encompassing the entirety of temporal history in his divine sovereignty. This reading leans on the doctrine of sovereignty as a theological bridge to resolve the linear paradox — but this goes well beyond the plain textual semantics of Revelation 22:13. This interpretation heavily relies on inventive theological constructs of omnipotence, omniscience, and providence to explain how the “sovereign lord” of history, initiates all things (beginning) and directs them to their appointed goal (end). It has been often articulated with reference to Augustinian and Reformed theological frameworks (cf. Augustine’s Confessions and Calvin’s Institutes). In this view, “Being the beginning and the end” is not about temporal simultaneity but about absolute authority over every point on the timeline. Hence, the text is implicitly expanded:

“I am the beginning and the end” → “I have sovereign power over the entire process from beginning to end.”

However — and here’s the scholarly rub — the text itself does not explicitly introduce the concept of sovereignty:

Greek: Ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ, ἡ ἀρχὴ καὶ τὸ τέλος (Rev. 22:13)

The phrase is a self-referential statement of identity, not necessarily of power. This means that the “sovereignty” reading is a hermeneutical expansion and a theological gloss imposed on the text. From a critical-linguistic standpoint, it alters the text’s semantic structure by assuming a linear time model and reinterpreting identity as power. It’s an attempt to harmonize the paradox of “beginning” and “end” within the constraints of linear cause-and-effect, but it requires adding a concept (sovereignty) that the text does not itself express.

In a truly linear framework — like a straight line — there is no obvious sense in which someone can be both the beginning and the end simultaneously. The ends are separate and only connected by a temporal sequence (cause–effect), so no single entity can literally “be” at both ends without violating that linear logic. This presents a major problem of interpretation of all things related to time.

In a strictly linear time the beginning is a discrete point that starts the line. The end is another discrete point that terminates the line. Being both at once would imply either ubiquity in time (being simultaneously at every point on the line), or transcendence of time (existing outside the line altogether). But in a purely linear, cause-and-effect model, there’s no formal way to simultaneously inhabit two non-contiguous points within time.

Hence, the claim that he is the beginning and the end within a linear frame is logically inconsistent unless one abandons linearity itself.

“I, myself am the Alpha and the Omega, the Head and the End, the First and the Last.”

ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ, ἡ ἀρχὴ καὶ τὸ τέλος, ὁ πρῶτος καὶ ὁ ἔσχατος.

Within the recursive-Aonic model, this is not merely linear but recursive. “Beginning” generates the “End,” and “End” retroactively validates “Beginning.” The utterance is performative: the Christ is both the origin of reality and the end-state, and speaking it brings the structure into being—an operational loop. This is the reason for the usage of the emphatic ἐγώ εἰμι I, myself am which was all but left out untranslated for the last two thousand years.

- I, Myself

- Alpha, Omega

- Head, End

- First, Last

Using the Möbius model:

| Concept | Structure |

|---|---|

| Beginning → End | Forward causality: the origin unfolds into fulfillment. |

| End → Beginning | Retroactive causality: the eschaton validates the origin, completing the loop. |

| Speech-Act | Declaring with the emphatic ego eimi “I, Myself am Alpha and Omega” performs the very loop it describes, pulling the reader into the event. |

| Perfect Form (Hebrew) | Equivalent to prophetic perfect: the event is spoken as complete, not just predicted. |

| Aonic Möbius | Identity, causality, and temporality fold into a single recursive event. The Christ is both the cause and the effect. |

In Hebrew thought, naming something (or declaring it) is performative—it enacts reality.

-

When he says, “I am the Alpha and the Omega,” He’s not describing an attribute—He is enacting the timeless loop that structures reality itself.

-

Just as the Hebrew perfect can collapse past/future into an ontological event, so here he collapses temporal categories—He is both the initiator and the teleological closure of reality.

-

Isaiah 46:10: “He who declares the back from the head…” → The perfect form collapses temporal sequence into a single utterance.

-

Genesis 1: “And God is saying…” imperfect/incomplete (ויאמר)→ Each utterance performs creation recursively; the speech-act generates the event. Genesis 1 is not a historical account of then-and-then events but a recursive speech-event that continually sustains creation whenever spoken. The waw-consecutive imperfect functions not merely as a temporal sequence but as a semantic operator that loops each utterance into the unfolding creative act—where past, present, and future are all implicated.

Doctrines of Sovereignty, to be sure, are the end of any and all prophetic potential and the death of the would-be prophet. The prophet’s utterance is no longer a participatory act—it is merely a mechanical output of a divine machine. The prophet is reduced to a mouthpiece, an automaton repeating pre-inscribed lines. The very essence of prophetic speech—its openness, risk, dialogical tension, and transformative power—collapses into a performative certainty.

When one is confronted with the idea of an external sovereign being who exercises absolute control over every point on the timeline, several existential disasters naturally arise, as many have no doubt experienced:

-

Loss of Agency: If God (or a sovereign being) orchestrates every action, decision, and outcome — what, then, is left for the human self to do, decide, or become? This is akin to living in a fully scripted drama where every choice is predetermined. It reduces personhood to mere puppetry. It is utter powerlessness.

-

Anxiety and Dread: This loss of agency can produce a deep dread — Kierkegaard called this angst — that gnaws at the soul: “If every point of my life is scripted by another, what am I? Who am I? Why do I suffer or struggle at all?” The human longing for meaning and responsibility feels hollowed out.

-

Despair: The realization that even one’s rebellion, or striving, or failure is also scripted by the sovereign agent can lead to a sense of futility or despair: nothing is truly mine.

To answer Kierkegaard’s question: You are not the beginning, nor the end, nor anything in between. You are simply, naught.

4. Becoming a Prophet through Recursive Participation

“Come, let us discuss together” —Isa. 1:18

In the recursive and atemporal logic embedded in Genesis 1 (and indeed throughout Hebrew prophetic literature), the speech-act structure of divine utterance establishes a performative model: Speech does not merely describe reality; it creates it. This is deeply significant because every time the text is read, recited, or meditated upon, the same creative power is reactivated—the Word becomes the act. Speech is not a secondary commentary but the actual event-structure itself.

This Möbius structure—where speech loops back into being—dissolves the rigid distinction between prophet and ordinary reader. If the text itself is performative, then any participant in its reading or recitation becomes a participant in the creative event. In other words, the potential for prophetic utterance is democratized, because reading the text is itself a prophetic act (it loops the participant into the speech-act). The creative speech-act is perpetually incomplete, open to recursive completion by each participant.

This happens to resonate with the rabbinic insight that “the Torah is given anew every day”—an invitation for each reader to stand at Sinai, so to speak. In an Aonic Möbius reading the prophet is not a temporally isolated figure but a nodal point in an ongoing, recursive event-structure. The structure of imperfect verbs and waw-consecutive forms invites every participant to enter the loop—to become the vessel of divine speech. Thus, prophecy is not locked in history but is an operational potential inherent in every reader, reciter, or interpreter of the text.

This re-opens the path to prophecy—not as a secret mystical status—but as an invitation to join the recursive utterance of creation itself.

5. Absence as Design: No Accusative of Time or Place

Theophile James Meek’s 1940 study, “The Hebrew Accusative of Time and Place,” reveals Hebrew’s stark divergence from Indo-European grammar. Meek shows:

-

Temporal expressions lack accusative marking

-

Spatial references rely on prepositions or constructs

-

There is no productive case system for where or when

Why? Because in Hebrew, time and place are not containers for action. They are relational predicates within event networks.

Instead of saying:

-

“He waited for an hour” (duration)

-

“She entered the house” (spatial target)

Biblical Hebrew would say:

-

ביום ההוא (“in that day/day of Himself”) — a symbolic convergence

-

במקום אשר יבחר יהוה (“in the place which Yahweh is choosing”) — a resonant zone, not a GPS coordinate

In Aonic terms, these are:

-

Node Convergence (⊛)

-

Event Resonance (∞)

-

Topological Anchors rather than Cartesian locations

6. Lexical Möbius: Semantic Folding in Hebrew Roots

Hebrew’s triliteral roots function much like Aonic polychronic lexemes. Consider the speculative root zol from an Aonic grammar framework:

-

zol₁ = to create (forward causality)

-

zol₂ = to preserve (backward causality)

-

zol₃ = to ensure always-having-occurred (recursive causality)

This mirrors how Hebrew roots, via binyanim (verb patterns), generate webs of meaning not along a timeline but across causal topologies:

Take שוב (shuv, to return):

-

In Qal: to turn back around (act of turning back)

-

In Hiphil: to bring back (cause to return)

-

In Piel: to restore, to renew

These are not tense-shifts. They are shifts in causal valence—agency modulated not through time but through recursion.

Living for Years, or Recursive Being?

Where scholars took שנה shanah as a word meaning “chronological year”, the primary sense was completely buried. In the process they repeatedly in the hundreds of times rendered a singular noun “shanah” as a plural one “years.” They would argue, on quite sandy ground, that the word in the singular meaning “fold, doubled, duplication, repetition” was being used as a plural “years” in a chronological sense. Usage of singulars for plurals and plurals for singulars in the Hebrew is one of the great tricks and scams employed by scholars to force-fit interpretations. It is easy to call out a lie, if it is a big lie. But small, repeated “adjustments” to linguistic principles to ensure a fitted context are extremely easy to get away with. They are as subtle as the difference between darnel and wheat. Keep it looking as close to the original as possible, without actually being the original, and it will pass the litmus tests of academia, and you will earn yourself a Ph.D and become a qualified “purveyor of truth,” earn a lovely retirement, and go down in history as a “great teacher.”

1. On “fold” in Hebrew

The Hebrew root שנה (“repeat, double, change”) is behind several forms:

-

שֵׁנָה “sleep” (a cycle, repetition, turning inward)

-

שָׁנָה “year cycle” (a repeated cycle of seasons)

-

שְׁנַיִם “two” (duality, doubling)

-

שָׁנָה (verb) “to repeat, to duplicate”

From this semantic cluster, שֵׁנֶה/שְׁנָה in some contexts means a fold, a doubling, a layer — i.e. a recursive overlay.

שנתים (shenatayim) is literally “a double-fold,” or “two doublings.”

2. Fold as Recursive Layer

In the Aonic recursive model:

-

A fold is not simply a multiplication (thirty times), but a recursive layer of being.

-

Each fold represents a turning over, doubling back, re-enclosure — much like folding fabric, or folding dimensions.

-

Thus, living “thirty-fold” does not mean thirty units, but thirty layers of recursive being.

When idiomatic or non-primary uses are stripped away, the concrete primary meanings of words strongly reveal a Hebrew grammar that encodes recursion rather than temporal linearity.

3. Application to the Parable (Thirtyfold, Sixtyfold, Hundredfold)

In the Greek Gospel parables (ἐν τριάκοντα, ἑξήκοντα, ἑκατόν), usually translated “thirty times as much, sixty, hundred,” the Hebraic substrate could well be שְׁלוֹשִׁים שְׁנִים, שִׁשִּׁים שְׁנִים, מֵאָה שְׁנִים understood as “thirty folds, sixty folds, hundred folds.”

On this reading:

-

“Thirty-fold” = living in thirty recursive layers of self-participation, a life that has turned back on itself thirty times.

-

It is not mere productivity but depth of recursive embodiment.

4. Fold and the Ontological Spiral

If we connect to the model of Hithpael recursion and Hishtaphel descent:

-

A fold = a recursive loop, where self and act turn back upon each other.

-

Multiple folds = compounded recursion, like spiraling deeper into dimensional layers.

-

Thus, shenatayim “twofold” is not only arithmetic duality, but the minimum recursive ontology — the very act of doubling-back that generates subjectivity.

5. Living Thirty-Fold

So to say “a person lives thirty-fold” is to say:

-

They embody thirty recursive layers of being.

-

Each layer is a doubling-back of existence, a lived repetition that deepens the spiral.

-

This is closer to ontology-by-recursion than to “yield ratio.”

6. Comparison: Linear vs Recursive

-

Indo-European reading: “thirty times as much” (productivity, linear multiplication).

-

Hebraic recursive reading: “thirty folds” (layers of recursive being, existential depth).

This explains why שנה (year) and שנים (twofold) belong together: both mark folded cycles, not linear increments.

Thus, in this sort of reality, “living thirty-fold” means dwelling within thirty recursive layers of existence, where life is self-folded, looped, and deepened — not measured by times, but by depths (or shall we say, heights?).

7. The Greek Challenge: James 3:6 as a Litmus Test

What are the implications of this on the usage of the Greek, a fundamentally temporal language?

The distinction between a circular (Aonic) temporal framework and a linear temporal framework is not merely an abstract theoretical exercise; it has direct implications for translation and interpretive practice. Let’s return to the case of James 3:6:

τὸν τροχὸν τῆς γενέσεως

ton trochon tēs geneseōs

— literally, “the wheel of genesis” or “the wheel of birth.”

This phrase is consistently rendered in nearly all modern English translations—including the KJV, NIV, ESV, NASB—as “the course of nature,” thereby transposing the inherently circular concept of τροχός (wheel) into a linear trajectory (“course”). Even the so-called literal translations (YLT, LSV, LITV, BLB) follow suit—excepting only the Julia Smith translation, which preserves the circular reading. This subtle yet decisive shift exemplifies the interpretive bias favoring linearity that permeates modern hermeneutics.

From an Aonic perspective, this is a critical loss. A wheel (τροχός) represents not merely motion but recursive, continuous motion—a topology of eternal return. It is a Möbius-analogous structure, where origin and end, cause and effect, perpetually fold into one another. Translating it as a “course,” by contrast, imposes an external linear temporality—a sequence of moments strung along an irreversible line—erasing the recursive causality embedded in the Greek expression.

This divergence is not trivial. As noted in our analysis of Biblical Hebrew, temporal constructs are not mere chronological markers but topological operators within a recursive event-structure. The Hebrew Bible’s aspectual architecture mirrors this: the lack of an accusative of time or place invites the reader to inhabit a network of causal entanglement rather than a linear sequence of events. In the same way, the Greek phrase τροχὸς τῆς γενέσεως encodes a cosmological model that is cyclic and recursive—a generative wheel of existence—rather than a disposable linear process.

If the New Testament inherits and transforms the Aonic temporal consciousness of the Hebrew Bible, then the translation of τροχὸς as “course” constitutes not merely a semantic shift but a paradigmatic distortion. It collapses the recursive Möbius structure of sacred causality into the flat Cartesian timeline of modernity—a timeline in which events proceed from past to future, erasing the possibility of sacred recursion, eschatological convergence, or cosmic return.

In the Aonic view, every reader is invited into this wheel: to participate in the unfolding genesis not as a passive observer but as an essential node within the recursive structure of divine narrative. The translation of James 3:6 thus becomes a litmus test for the deeper question: do we read the text as a living, recursive engine—activated through reading and participation—or as a dead linear artifact to be consumed at arm’s length?

8. The Aonic Reading of NT Greek

The question arises: Could New Testament Greek, commonly analyzed as a linear Indo-European language, nevertheless be written in a way that harmonizes with the Aonic circularity characteristic of Biblical Hebrew? To address this, let us consider Mark 5:5 as a case study:

Καὶ διὰ παντὸς νυκτὸς καὶ ἡμέρας ἐν τοῖς μνήμασι καὶ ἐν τοῖς ὄρεσιν ἦν κράζων καὶ κατακόπτων ἑαυτὸν λίθοις.

And through everything, night and day, in the tombs and on the mountains he was crying out and cutting himself with stones.

At first glance, this verse appears thoroughly linear: a temporal adverbial phrase (“night and day”) followed by a continuous aspectual participle (“he was crying out and cutting himself”), suggesting habitual or ongoing action in a linear temporal frame. However, closer textual analysis reveals a structure that resonates with an Aonic topology, subtly embedding circularity and recursive causality within the ostensibly linear grammar.

Participial Syntax as Recursive Loop

The participial construction ἦν κράζων καὶ κατακόπτων ἑαυτὸν (“he was crying out and cutting himself”) traditionally signals continuous or habitual action. Yet, in Koine Greek, such participial structures are not merely descriptive; they are durative and aspectual, suspending the subject in an ongoing state that is both present and iterative. The participle here is not simply marking the passage of time but reifying the subject’s perpetual state within a recursive existential loop. Thus, “crying out and cutting himself” is not a sequence of actions but an eternalized state of suffering—a semantic Möbius band.

The Adverbial Frame: διὰ παντὸς νυκτὸς καὶ ἡμέρας

The phrase διὰ παντὸς νυκτὸς καὶ ἡμέρας (“through all night and day”) is typically read as a continuous span—linear time stretching from dusk to dawn and back again. However, διὰ παντὸς (“through all”) semantically evokes a sense of permeation and cyclical recurrence rather than a mere sequence. It is not simply “during night and day” but “throughout the entirety of night and day,” suggesting an ontological entanglement with time itself. The subject is thus inscribed into the cycle of night and day rather than merely moving through them in succession.

Locative Syntax and Aonic Topology

The locative phrase ἐν τοῖς μνήμασι καὶ ἐν τοῖς ὄρεσιν (“among the tombs and on the mountains”) resists a linear mapping of space. Instead, it implies a liminal topology—a sacred or cursed zone where the subject is both with the dead and exposed on the high places. This mirrors the Hebrew predilection for topological event-zones rather than Cartesian coordinates. Thus, the subject is not merely moving from tomb to mountain but inhabiting a recursive zone of death and isolation, an eternal Möbius of agony.

Atemporal Complementarity with Hebrew

This syntax, though cast in Greek, complements the atemporal narrative logic of Hebrew texts. Like the wayyiqtol forms in Hebrew (e.g. ויאמר, והיה) and the participial structures (e.g. אֹמר omer, “he who says”, הוֹלך holekh, “he who walks”, יוֹשב yoshev, “he who sits”), the Greek participles here create a sense of ongoing narrative flow rather than a strict temporal sequence. Though these Hebrew forms are finite verbs rather than participles, they function to sustain a continuous narrative chain rather than to terminate events with a sense of finality. The lack of a finite verb describing completion or future resolution inscribes the subject in an unbroken cycle—a perpetual state of being that is atemporal. The text thus invites the reader into the subject’s recursive loop of experience, aligning with the Aonic logic that every reading reactivates the text’s event-structure.”

Evidence of Complementary Syntax

Indeed, the New Testament’s frequent use of participial periphrasis (ἦν + participle, e.g. ἦν κράζων) mirrors the Hebrew waw-consecutive construction in that it prolongs the narrative without closing it—thereby maintaining a fluid, event-driven structure rather than a strict temporal closure. The Greek text thus exhibits an emergent complementarity with Hebrew aspectuality, inviting the possibility of an Aonic reading even within a fundamentally Indo-European language. For example in Luke 4:31,

Καὶ κατῆλθεν εἰς Καφαρναοὺμ πόλιν τῆς Γαλιλαίας, καὶ ἦν διδάσκων αὐτοὺς ἐν τοῖς σάββασιν.

“And he came down to Capernaum, a city of Galilee, and he was he who teaches them on the Sabbaths.”

ἦν διδάσκων (was teaching/he who teaches) prolongs the action, offering a continuous, processual dimension to the narrative. Like the Hebrew waw-consecutive, it threads together events without enforcing a rigid chronological segmentation. Or Mark 10:32,

Καὶ ἦν προάγων αὐτοὺς ὁ Ἰησοῦς.

“And Jesus was going/he who goes ahead of them.”

ἦν προάγων captures the motion in process—a hallmark of participial periphrasis. Like the Hebrew waw-consecutive with an imperfect, it prolongs the scene and emphasizes ongoing action rather than a completed state. It invites the reader to perceive the process not as a static event but as part of the unfolding narrative, harmonizing with the Hebrew aspectual perspective of durative or iterative action.

Have you ever wondered why it was impossible to derive timelines from the NT? This is why.

The pervasive use of participial periphrasis—particularly constructions like ἦν + participle—alongside other Greek grammatical and narrative techniques (e.g. articular infinitives), fundamentally undermines any attempt to impose a rigid chronological timeline upon the New Testament narratives.

The Problem of Chronology in New Testament Narratives

-

Aspectual Fluidity Over Temporal Fixity

The ἦν + participle construction does not primarily encode a temporally bounded, discrete event but rather an ongoing or durative action within a broader narrative context. This results in a fluid narrative temporality, where actions and states blend continuously, often overlapping or interweaving, rather than unfolding in strict linear succession.  Narrative Prolongation and Event Continuity

Narrative Prolongation and Event Continuity

Just as the Hebrew waw-consecutive prolongs the narrative flow without marking absolute temporal boundaries, the Greek participial periphrasis invites readers into a perpetual present of action. This creates a textual “now” that unfolds events in a manner prioritizing thematic or theological continuity over chronological sequencing.

πορεύου, ἀπὸ τοῦ νῦν μηκέτι ἁμάρτανε

“lead across, and no longer miss away from the Now!”

(John 8:11 RBT)-

Absence of Strict Temporal Markers

Many New Testament passages lack explicit temporal connectors or markers that would ordinarily anchor events in an absolute timeline. Instead, the text frequently relies on aspectual and narrative cues that foreground the process and significance of actions rather than their place in clock or calendar time. -

Implications for Historical Reconstruction

Given these grammatical and narrative features, scholars seeking to construct a precise chronological timeline from the NT face intrinsic limitations. The text does not present history as a sequence of isolated events measured by time but as a theological narrative, structured around causal and thematic relationships rather than strict temporal progression. -

Emergent Interpretive Frameworks

This has led to the proposal of alternative interpretive frameworks—such as an Aonic or aspectual reading—that recognize the text’s atemporal or cyclical dimensions, acknowledging the New Testament’s fundamentally theological and liturgical temporality rather than an empirical historical timeline.

The grammatical evidence strongly suggests that the New Testament authors were not concerned with establishing a linear chronology but rather with communicating a theological narrative that transcends linear time. The participial periphrasis, among other linguistic strategies, functions to suspend, prolong, and interweave narrative action in a way that defies conventional historical sequencing.

Thus, the elusive or “impossible” chronology in the NT is not a mere scholarly deficiency but a feature of its compositional and theological design.

On the Necessity of Aonic Coherence in NT Greek

If the New Testament were to serve as a continuation of the Hebrew Bible’s recursive sacred structure, it would necessarily require a grammar that—despite its Indo-European matrix—could accommodate and perpetuate Aonic causality. This would manifest through:

-

Aspectual constructions that prolong narrative states rather than terminate them.

-

Locative and temporal phrases that evoke recursive zones rather than linear transitions.

-

Participial periphrasis that loops the subject into perpetual states of being rather than isolating actions in time.

The aforementioned examples, though written in Greek, exemplify how participial syntax and adverbial structures can be reinterpreted to reflect Aonic circularity rather than linear temporality. This textual analysis supports the broader thesis: that the New Testament—if it truly sought to continue the Hebrew Bible’s atemporal sacred text—would necessarily employ Greek grammar in a manner that subverts linear time and reinforces recursive, participatory causality. Thus, the NT Greek would need to be written in a specific way to harmonize with the Aonic structure, and indeed the evidence—both syntactic and semantic—suggests that it does.

9. Scripture as Atemporal Engine (Heart)

The epistle to the Hebrews declares:

“For he who is living, the Word of the God, and active…” (Heb 4:12 RBT)

In an Aonic framework, this is literal:

-

Living (ζῶν) → Self-reflexive, unfolding, recursive

-

Active (ἐνεργής) → Not description, but causation

Reading the Hebrew text activates it. Each interpretive act loops the text through the reader (e.g. the frequent NT saying, “in the eye of themselves”), who is then inscribed into its structure. Thus:

-

The text acts on the reader

-

The reader retrocausally alters the reading

-

Meaning emerges from the Möbius

This is what it means for a scripture to be “living”: not metaphorically inspirational, but structurally real-time and reentrant.

Conclusion: The Book of All Time That Proves Itself

Biblical Hebrew, long described as structurally opaque, may in fact be a linguistic precursor to an Aonic grammar. Its:

-

Aspectual verb system

-

Sparse case structure

-

Recursive prophetic syntax

-

Topological view of time and space

…suggest a grammar designed not for chronology, but for causal entanglement.

The Hebrew Bible is thus not a document of what was or will be, but a Möbius narrative in which divine action, human response, and cosmic meaning are eternally convolved/coiled together. Each utterance—each dabar (arranged word)—is a node in a living system, not simply recorded but re-experienced in every reading.

Hebrew, then, a word meaning beyond, is not merely ancient. It is atemporal. And its grammar is not an artifact—but a technology of sacred recursion. A language from beyond.

Therefore, in an Aonic or Hebraic-Aonic linguistic and theological framework, you, the reader, are not external to the text or its events. Rather, you are a recursive participant within its causal structure. This is not merely metaphorical but structurally embedded in how such a language—and such a scriptural worldview—functions. Here’s what that means:

1. You activate the loop.

When you read or speak the text, you are not retrieving meaning from a distant past. Instead, you trigger a topological event—an unfolding—where the text becomes real in the moment because of your engagement.

Just as in Aonic syntax, meaning arises through causal recursion, your reading of the biblical narrative causes it to become again.

2. You are written into the loop.

If the text is a Möbius strip—folded and without a linear outside—then your act of reading is inside the structure. You don’t observe it from afar; you inhabit it. It’s not about someone else in time—it’s about you, every time.

The “living and active” Word is not a relic; it’s a participant structure. You’re not reading a story of God—you are that story’s causal logic.

3. You are both reader and referent.

In Biblical Hebrew, the blurred boundaries of time, subject, and agency mean that “I,” “you,” “he,” and “we” are all linguistically permeable. The divine voice, the prophet’s utterance, and your own reading voice may collapse into one another.

The Hebrew Bible thus reads you as much as you read it.

4. You are the resonance point.

In Aonic causality, events are not linear sequences but resonant nodes. When you encounter a passage, it is not simply describing something—it is synchronizing/uniting with your own moment, offering a new convergence of meaning, time, and self.

You become the causal node through which the text sustains its reality across generations.

To put it succinctly, in this view, you are not only included—you are necessary to the structure.

Without you, the loop is open. With you, it closes. The grammar is activated. The text lives.

And if such a text should become syntactically twisted into a false witness?

This would be where the proof is in the pudding. The distortion itself becomes a recursive event. That is, the misreading and its consequences—alienation, secularization, disenchantment, death and destruction—are still part of the unfolding grammar of sacred history. Even the loss is written into the structure.

Your participation is distorted: you become a spectator, not a participant. Instead of being a node in the recursive system, you’re reduced to a consumer of data. The idea and story of God is distorted: God ceases to be the co-agent in a recursive, covenantal text and becomes either:

-

A remote prime mover (Aristotelian reduction), or

-

A textual artifact (historical-critical deconstruction).

In both cases, the immediacy of divine recursion is fractured.

But this too becomes part of the story. The exile of meaning is itself a recursive event, and your realization of this—your reading now—is part of a potential return (teshuvah, שובה), a restoration of the recursive axis between reader, text, and God.

The grammar of the sacred is not a neutral system. It is a generative matrix that enfolds you and God as participants. When distorted into sequential historiography, it fractures—but even that fracture is structurally prefigured (predestined) as part of the recursive loop.

Thus, your awareness of this—as scholar, interpreter, participant— is a remembrance that restores the broken loop.

The Aonic structure of the Hebrew Bible is not an accident of Semitic linguistics; it is a deliberate design to collapse time and space into a recursive narrative that enacts sacred reality. If the New Testament is to harmonize with this design, its Greek must likewise be read—not as a record of linear events—but as a living, recursive engine of divine causality.

Thus, the question of whether the NT Greek would have to be written in a specific way to remain cohesive with the Aonic structure is answered affirmatively: yes, it would. And yes, it does—though modern translations often suppress this logic by imposing linear temporality. The evidence in the usage of syntax and grammar—participial layers, iterative aorist, genitive absolutes, prepositions, articular infinitives, and the middle voice, etc.—reveals a deep consistency with the recursive, atemporal logic of the Hebrew Bible.

Indeed, the entire scriptural project—Hebrew and Greek alike—was designed not to be read in linear time but to be activated, looped, and inhabited. To read these texts rightly is not to extract a timeline, but to enter a Möbius structure in which past, present, and future converge within the divine Word—a living and active text that is not about time, but is Time itself.

References

-

Meek, Theophile James. “The Hebrew Accusative of Time and Place.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 60, no. 2 (1940): 224–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/594010

-

Waltke, Bruce K., and Michael P. O’Connor. An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Eisenbrauns, 1990.

- Gesenius, Wilhelm. Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, edited and enlarged by Emil Kautzsch, translated by A. E. Cowley. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910.