Proverbs 16:33 says:

“The small stone is caused to be cast into the Fold/Bosom, and every decision/judgment is from HE IS (“YHWH”).”

This verse might sound like it’s just about chance—like flipping a coin and hoping God makes it land the right way. But in Hebrew, it’s much deeper.

Let’s break it down:

- גורל is defined as “1. (properly) a pebble.” It is the proverbial Small Stone, cast or hurled forth. (Strong’s #1486)

-

The phrase “cast into the Fold” uses a Hebrew word (יוטל) that means “is caused to be thrown.” That means the person doesn’t really do the action directly—something bigger is guiding it.

-

The “lap” (or “fold”) was a place where people held things close. So it’s not just tossed into space—it’s put into a place that’s personal and hidden. The Bosom of the Eternal One.

-

And then the second part says: “But every judgment from Yahweh.” So even though it looks like someone is casting a lot (like drawing straws or rolling dice), the real decision was already known.

So what’s the bigger idea?

In our modern thinking, we often imagine time like a straight line: past → present → future. If you “cast lots,” you’re making a decision about the future, like choosing randomly what happens next.

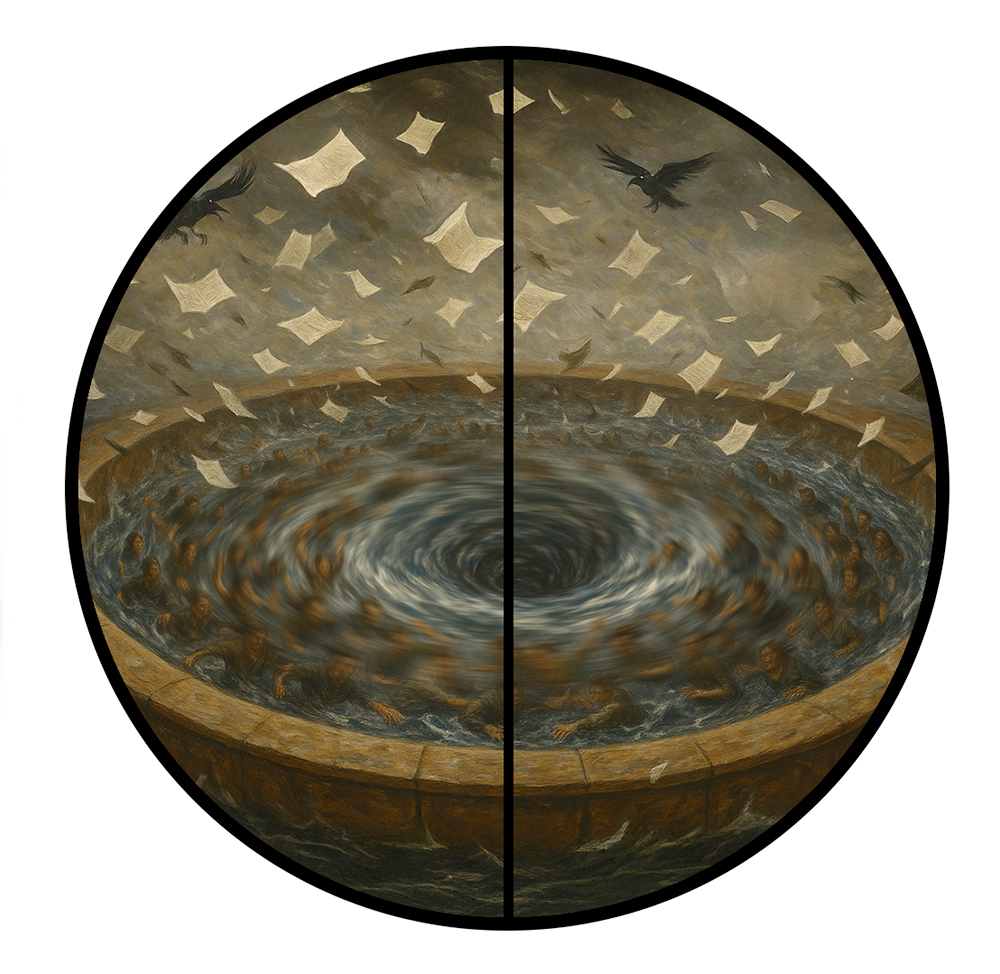

But in the Hebrew aonic (eternal) mindset, time is a wheel, with an outer rim, or loop. Casting the lot doesn’t create a new future—it reveals what was already woven into the plan. It’s like pulling back a curtain on something already there. Imagine you’re reading a story you’ve never read before. You think you don’t know what will happen next—but the ending is already written. Casting the lot is like turning the page: you’re not creating the next part; you’re just stepping into it.

Throwing the lot (casting it) is not just something that happens in the moment—it’s more like planting a seed that already knows how it will grow.

When you cast the lot, you’re not choosing a random future—you’re unfolding something that was already written inside. It’s like opening a letter that was placed in your hand long ago.

The “casting” doesn’t create the outcome—it reveals it.

And since the Hebrew uses a passive verb form (“the lot was caused to be cast”), it means:

You didn’t really throw it—it was thrown through you.

You were part of the process, but something beyond you was guiding it—like a hidden hand working through your action.

Casting lots in the Bible was never about throwing dice or flipping a coin. In the Aonic view, to “cast the lot” (הגורל) is not merely to drop a stone into a fold of cloth, but to inscribe a seed of participation into the Fold of time itself. That “Fold” (as in בחיק—the bosom or inner curve) is a Möbius-like space where origin and outcome are inseparable.

You do not cast something to see what will happen.

You are caused to cast to become part of what is already happening—what has always been happening, waiting for your act to complete the loop.

Imagine a scroll that writes itself only when you read it—and by reading it, you appear within it.

Casting a lot in the Aonic (eternal) sense is like dropping your name into that scroll—not to force a result, but to become a co-writer of the unfolding.

“Into the Fold the lot is cast, but every decision from HE IS” (Proverbs 16:33).

The act of casting is your consent to the unfolding, not your control over it.

“And the Lot fell upon…” (Acts 1:26)

Casting the lot is like opening the seed of your own story—a story already inside you, but only revealed when the right moment unfolds. It’s not about choosing the future—it’s about uncovering what was always there.

It’s not about gambling.

It’s not about prediction.

It’s about handing over—hurling away—a part of your being “the Small Stone” into the recursive structure of eternal sacred time—

where your act echoes, returns, and names you.

You hurl away the small pebble stone—the lot, the גורל—

and what returns is not the same.

It comes back to you,

but changed—

engraved,

sealed,

named.

To the one who conquers… I will give a white small stone,

and upon the small stone a new name is written,

which no one knows except the one who is taking hold.

— Revelation 2:17 RBT

The cast stone becomes the name-stone.

The lot becomes the Word.

The throw becomes the turning back.

“Men of Judah”

In the Aonic logic of Scripture, the act of casting is not abandonment. It is consecration.

You entrust the seed of yourself into the timeless Fold,

and in that recursive grammar, the Word throws you back—

but you are now named.

What was cast in uncertainty

returns as identity.The stone that was flung

becomes the cornerstone of the self.

The name “Judah” (יהודה) is traditionally derived from the Hebrew root ידה (yadah), which at its core means:

-

to throw, to cast, to shoot forth,

and in extended senses, -

to confess, to praise, to acknowledge.

This meaning opens up a profound Aonic reading:

Judah is not merely “he who is praised,” but he who casts—

one who projects outward into the Fold:

an act of entrusting, of praising, as sowing,

to reap an eternal self who is praised, trustworthy, colossal.

Judah is the one who dares to throw.

Not recklessly—but in trust, in narrative surrender.

He casts forward a word, a confession, a praise,

and in doing so, he writes himself into the unfolding of the story of God.

This is why Judah becomes the lineage of kings,

the tribe of the Messiah,

the source of the Word made flesh—

because he embodies the casting that makes the return possible.

Just as the lot is cast into the fold (בחיק),

so too Judah casts himself into the desire of HE IS,

and from that casting emerges all judgment, all decision, all future, from and to himself.

Hence the meaning deepens:

Judah is the archetype of the one who casts and is cast—the one who becomes alive from and to himself.